Closer to home

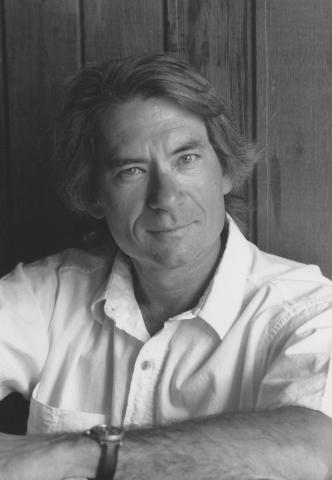

A personal account of writer Louis Owens

Louis Owens was not successful as a doctoral student in the ASU Department of English. He attended during 1975-76. Before dropping out, Owens accomplished only three credit hours—and that was for a Steinbeck course, an author on whom he went on to become a leading expert. He was an editor of Steinbeck Review (current Department of English member Kathleen Hicks is now an editor of the journal).

Instead of doing his doctoral coursework, according to a friend, Owens was staying up late to “monkeywrench” billboards from Phoenix to Flagstaff with a chainsaw. Owens picked up excellent chainsaw skills as a US Forest Service ranger and firefighter, skills he used to follow the inspiration of Edward Abbey’s famed radical environmental novel, "The Monkeywrench Gang."

For a while, Owens remained torn between English studies and the wilderness. He applied to what was then called the Yale School of Forestry, but went on to take his doctorate in English from the University of California-Davis. After teaching at The University of New Mexico and the University of California-Santa Cruz, Owens returned to UC Davis as Professor of English and Native American Studies and director of that English department’s creative writing program. Owens, one of the best-known scholars of Native American literature, committed suicide in 2002 at age 54.

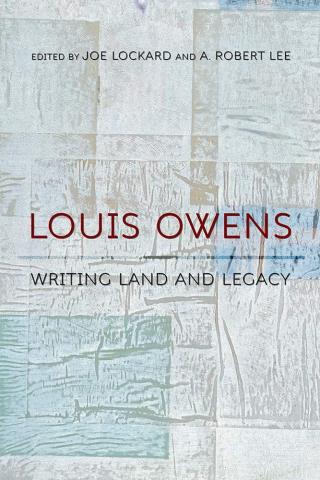

I was both a student and later a faculty colleague of Owens. Recently, together with A. Robert Lee, I published an edited volume, "Louis Owens: Writing Land and Legacy" (University of New Mexico Press, 2019).

Owens and I were friendly, but not close. At Davis, it was a lunch once-a-semester sort of friendship. He brought a bag lunch; I brought my usual chicken salad sandwich on whole wheat bread. I held a two-year fellowship appointment and Owens was the only faculty member in the department with whom I had a history.

Owens and I first met at UC Santa Cruz where I was an older, married undergraduate student and our mutual friend (Native American writer) Gerald Vizenor had spoken of me. I signed up for his Steinbeck class, a large class that met in an auditorium. I was teaching a course in Middle-eastern literature in the period immediately before, so I was tired and quiet in his class. Apparently, he was expecting great things from me as a student and I did not meet initial expectations. When I finally made a comment about two-thirds of the way through the course, Owens exclaimed to his graduate assistants after class: “He spoke, he spoke, he finally spoke!” Eventually I came to know Owens and his wife Polly over a grill in our backyard in a Bay Street rental home to where I had evacuated my family from under Saddam Hussein’s missiles.

Together with scholarship on Native American literature and John Steinbeck, Owens wrote crime fiction that established his name as a novelist. You could see how pleased he was when the New York Times Book Review published a front-page review of his novel The Sharpest Sight where the reviewer confessed that Owens had faked him out in the story and he had to re-read the novel to understand how. Owens had a good sense of humor and enjoyed pointing that out.

Readers will keep returning to Owens because the well is deep.

Owens was of Choctaw, Cherokee, and Irish descent in a family whose roots he discussed in an essay collection, "I Hear the Train" (University of Oklahoma Press, 2001). That origin gave rise to his critical discussion of “mixedbloods,” a term and concept that remains controversial among some Indigenous people and scholars of Native America. Owens presents them with a paradox. On the one hand, they acknowledge his foundational influence on Native American literary criticism in a book such as "Other Destinies: Understanding the American Indian Novel" (University of Oklahoma, 1994) and appreciate his novels. On the other hand, they reject his conceptual reliance on hybridity. As one critic phrased it, Owens’s work “is the unpleasant elephant in the room.”

I am part of the last generation of scholars—all of us getting on in years—who have the advantage of personal knowledge of Owens. The last two books of Owens criticism were published 20 years ago, although new critical essays and doctoral dissertations on Owens appear regularly. It seemed the right time to do this book. My co-editor, A. Robert Lee, was collaborating on a new project with Owens when he committed suicide.

Our book includes essays by Paul Whitehouse, Chris LaLonde, David Carlson, Billy J. Stratton, Alan Velie, James Mackay, Birgit Däwes, Cathy Waegner, Joseph Coulombe, and John Gamber, with a poetic coda by Diane Glancy and Kimberly Blaeser. Owens had a knack for inspiring friendship and his friends contributed to this volume. Several contributors are European. Owens, who spent a year in Italy as a Fulbright scholar and won France’s highest award for crime fiction for the 1995 translation edition of "The Sharpest Sight," has an international reputation.

What I came to realize more fully in doing this book is how much a working-class writer Louis Owens was. He came from a family that migrated from Mississippi to California, and lived in destitution in a tar-paper shack with linoleum flooring on bare earth. They were hungry and had damned little education. He was the first high school graduate in his family. Then working for United Can Company and intending to join the military, Owens started in higher education by taking an auto repair course at Cuesta Community College. He ended up an urbane scholar more-than-holding his own against top literary theorists.

Owens was proud of his origins and populated his novels with working-class characters. Except for one notable essay by Renny Christopher, criticism generally has overlooked this aspect of Owens’s authorial persona. Yet it is a key to much of his work and his encyclopedic devotion to Steinbeck, whose love of Salinas Valley and its working people he shared.

Owens once observed in lecture that a UC Davis colleague had commented, “Life is long and you might persuade me there is something worth reading in Steinbeck, but you will have to work very hard at that.” Ever the populist, Owens pointed towards such rejection as stigmatizing blue-collar labor and working-class stories. Owens denied using Steinbeck as a model in his fiction-writing, but the influence seems clear to most others. At the same time, Owens criticized Steinbeck for ignoring the genocide Euro-Americans committed against California’s native peoples.

Owens’s reputation today has drifted towards his environmental writing. Hundreds of nature writing anthologies and course readers have reprinted his “Burning the Shelter” account that reflects on the constructed nature of “wilderness.” ASU colleagues, including President’s Professor Joni Adamson, regularly teach his work.

Owens did not have a long career but it was richly productive. Readers will keep returning to Owens because the well is deep.

It was an extraordinary literary career for an ASU graduate school drop-out.

Image of Louis Owens used in Lockard's book, courtesy UC Davis Shields Library.