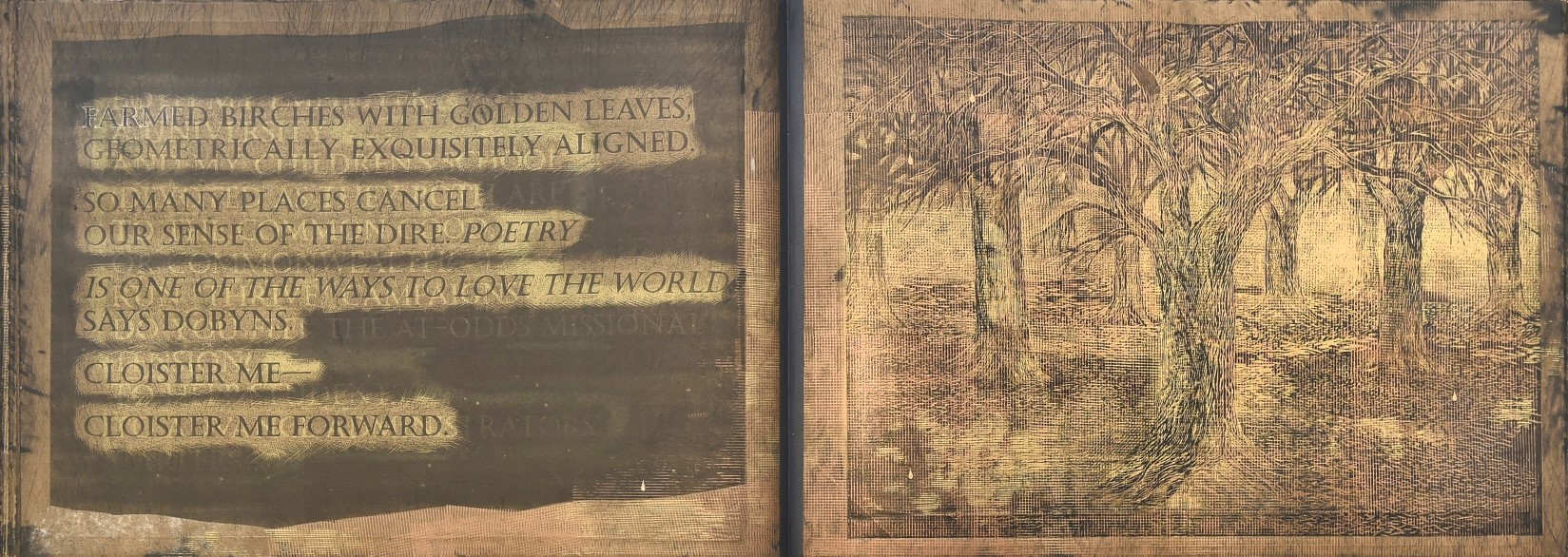

Wrangling the wild graffito

Containment and trickster discourse in a central Arizona university town

Editor's note: Teaching Professor Larry Ellis is a graduate of the Department of English at ASU, having earned an MA in 1997 and PhD in 2003, both in English literature. In October 2022 he delivered a version of this article at the Annual Meeting of the American Folklore Society in Tulsa, OK.

Just before the first outbreak of the COVID pandemic, a peculiar box-like object appeared on the corner of 7th Street and College Avenue in the university town of Tempe, Arizona. Measuring eight feet to a side, it was constructed of rust colored steel, and from a distance appeared as eldritch and out-of-place as the monolith that tormented and inspired humanity’s ancestors in Stanley Kubrick’s "2001: A Space Odyssey." Closer examination revealed something like a purpose. Each of its four visible walls bore prompts that invited passersby to share their thoughts. Chalk was provided on trays set at waist level and the cube was fully erased at intervals to make room for new entries.

Across the street from the campus of Arizona State University, the structure sat in one of the most heavily trafficked sections of the city. While the demographic of the area was largely associated with the university, it also included local residents, high school kids, service industry workers, religious evangelists, and homeless squatters. Potentially, all contributed to the textual dynamics of what was both a socially acceptable message board and a regulated graffiti venue for clandestine subversives lured, for a time, from their preferred on-campus and municipal targets.

At first glance, it appeared to be a public arts project, perhaps conceived to channel the graffiti impulse into a contained space, thus sparing buildings and walls in the area the attentions of the tagger’s spray can. Similar projects are widespread throughout the city. Most noticeable is a series of murals painted on utility boxes by local artists. Sponsored by the Downtown Tempe Community, a private, non-profit organization affiliated with the city, these arts spaces appear to be permanent fixtures, but without the dynamism of the ever-shifting surfaces of the graffiti cube. Both, however, seemed to work on the same premise: that the spontaneity of the graffiti phenomenon could be refocused to serve the public good and protect the integrity of public and private property. Tempe’s utility box murals seemed to bear this out, working within designated spaces and utilizing approved subject matter.

The graffiti cube on 7th and College was something different. Within its spatial boundaries anything was game, and a subversive discourse emerged in language and art that defied the inoffensive prompts that sought to control the activity on each of its four walls. Rude and often sexually explicit comments and drawings scuttled the cube’s attempt to foster civil discussion, and the substitution of permanent markers for erasable chalk by some participants further challenged the spirit of the project. Apparently, the marginalized voice of the renegade graffiti artist was appropriating the very instrument of its containment to reassert control over its message.

In his studies of the Native American trickster, post-modern theorist and novelist Gerald Vizenor speaks of trickster discourse, a destabilizing impulse that moves through texts, defying the master narratives that those in power employ to control and define those on the periphery. Throughout Vizenor’s fiction, tricksters both human and animal expose hypocrisy and challenge boundaries, playfully subjecting what he calls social science monologues and hyper-realistic interpretations of Native culture and literature to deconstructive scrutiny. The trickster, according to Vizenor, embodies the wild and comic in Native American literatures, and the chance and possibility inherent to both.

Graffiti is a wild and often comic folk genre, and when confronted with the threat of confinement and control may channel a figurative trickster as an agent of resistance. Mythologists William Hynes and William Doty’s description of the trickster as a situation inverter resonates in the transformation of the graffiti cube from a well-regulated discursive forum into the very thing it apparently wished to avoid—a crude, spontaneous free for all. We can almost see the trickster laughing over his shoulder as he moves on to new venues, new texts.

And move on he did. In several months, the graffiti cube vanished as suddenly and as mysteriously as it had first appeared. Call me superstitious, but I think the trickster saw me coming and decided that being subjected to the social science monologues of a pesky folklorist was the last straw.

At first, my inquiries to officials in the City of Tempe and the Downtown Tempe Community on the cube’s origins and history didn’t bear fruit. In fact, one of my contacts believed that it would have been highly unlikely that the city would have allowed such a project to go forward in light of its ongoing efforts to combat all expressions of graffiti through its partnerships with local businesses to eradicate it wherever it should appear.

Just when it seemed that the graffiti cube would continue to exist only in legend, I received an email from an official in the Business Improvement District for Downtown Tempe.

"We are responsible," she wrote,

- "for the ‘big cube’ that has been placed all around the downtown Tempe district for various uses over the last several years. The Cube made the rounds as a chalkboard in 2016 – 2017 with various prompts on it. Prompts included 'Before I Die I will…' and 'Believe….' The objective was simply to engage the community in conversation & expression. It was well received and we had very little hate or negative expression. Since that time, we have utilized the Cube for a canvas for giving congratulations to local high school graduates during the pandemic when graduations were canceled, a place for local artists to express themselves during the summer of 2020 and a place for general art expression. It currently sits in Centerpoint Plaza in front of the AMC movie theater, on 7th Street, just west of Mill Avenue."

The Business Improvement District of Downtown Tempe should be given credit for a fine project, but their success in maintaining civility on most of their message boards fell victim to trickster discourse on the cube’s visit to College Avenue and 7th Street. The prompts were similar to those mentioned above (“Before I Die I will…” and “Believe…”) and responses at first stuck to the program, but over time the ironic, the risqué, and the deconstructive took center stage, with declarations for Breitbart and Infowars chalked over arch social commentary and crude, pornographic sketch work. Prompts were either ignored or mocked. The trickster was clearly at play here.

For some time, Arizona State University has sought to similarly contain and channel the graffiti impulse. In Ross Blakely Hall, the home of the Department of English, portable white boards scattered throughout lobbies and hallways offer venues for informal, if prompted discussion.

In October 2022, students were greeted in the lobby of the department headquarters by a two-dimensional analog to the graffiti cube, addressed to the allure of pizza and monitored by the stern attentions of C3PO and his diminutive sidekick.

Sidewalk art and commentary, tied to projects approved by the university and supervised by university organizations and professors, is common, and at a project’s end is always erased.

But erasure as a strategy of containment can itself undergo situation inversion. In 2019, a series of graffiti appeared on the sidewalks of the university. Stenciled in black chalk, they provided directions to the Secret Garden, a secluded greenspace far removed from the hurly burly of campus life. Perhaps the artist acted with the best of intentions, but his handiwork violated the very spirit of the graffito. An avenging trickster erased the existing arrows and re-stenciled them to point in the wrong direction. Here, trickster discourse performed a valuable, if ironic, service in maintaining the sweet fiction of secrecy attached to this beloved memorial.

Which brings us to the adventures of Tempe’s ubiquitous Penis Man. In the years leading up to the COVID pandemic, his provocative scribblings on public and university property entertained students, faculty, and Tempe residents and confounded administrators and business owners. In January of 2020, a suspect was finally cornered by the law and arrested, booked on 16 counts of aggravated criminal damage, 8 counts of criminal damage, and one count of criminal trespassing. Apparently, his crimes were so heinous that the authorities needed to call in their big guns. “They raided my condo and vehicle,” mourned the culprit, “and swarmed my entire complex in West Phoenix with heavily armed SWAT officers and pointed a silenced assault rifle in my face.”

Claiming that he was only one in a broad-reaching community of Penis Persons, the Penis Man justified his tagging as an act of political protest targeting corruption in the Tempe City Government. And as if his offenses weren’t appalling enough, he dared to embellish the Arizona State University “A” on Hayden Butte with his distinctive signature. For decades, “A” Mountain has stood as a cherished landmark to university folk. At the beginning of each fall semester, first-year students participate in the time-honored ritual of whitewashing the letter, and guards are posted every year at the time of the homecoming game with the University of Arizona to protect it from vandalism. Clearly, Penis Man crossed the line here, a curious irony in that the big “A” is itself an act of sanctioned graffiti, and a questionable presence on a mountain that is sacred to the tribes of Southern Arizona’s Gila River Indian Community.

As the fluid identity of the Penis Man suggests, and trickster scholars Hynes and Doty confirm, the trickster is a shape shifter. Whether subverting the master narratives of public arts projects or sowing dismay and anger among city and university officials and businesspersons, he moves from place to place in different guises, impossible to pin down, laughing all the while at our confusion.

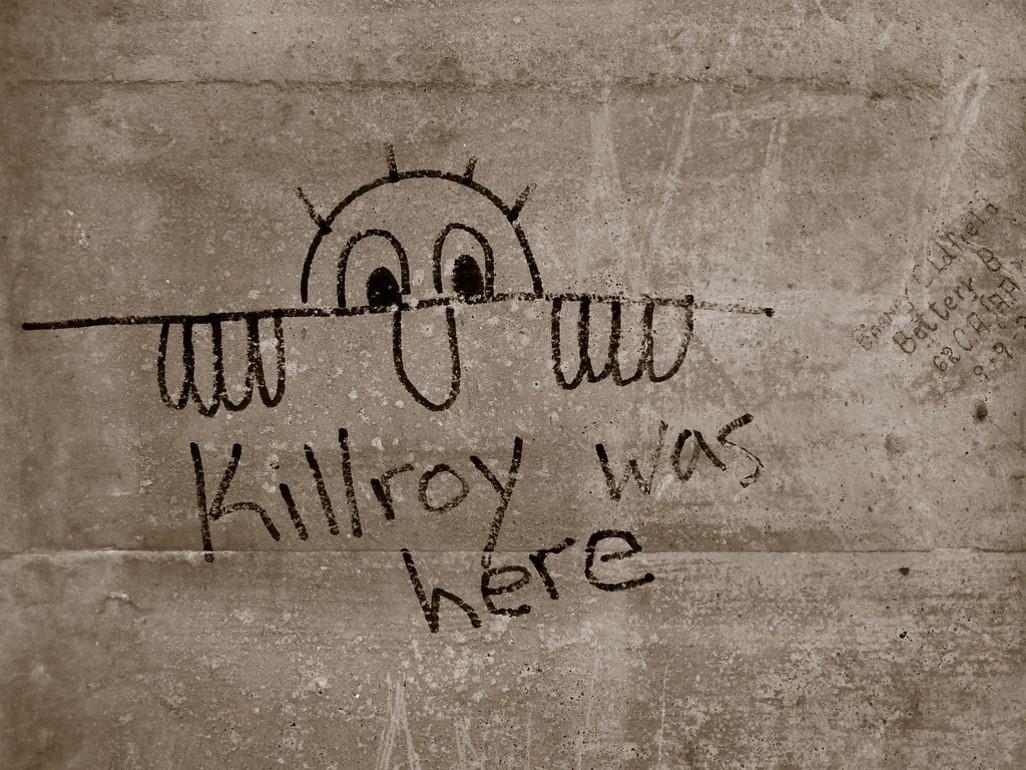

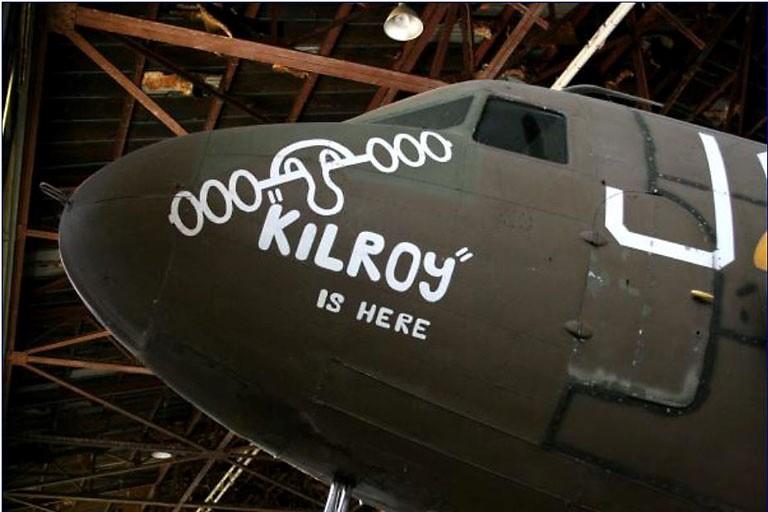

Image 1: "Kilroy was here" graffiti. Photo courtesy Larry Ellis

Image 2: A city of Tempe public art project, this utility box is painted with a mural, "Such is Desert Life" by artist Such Styles. Photo courtesy Tempe Public Art Searchable Map.

Image 3: A Graduation Chalk Wall—the repurposed "cube" described by the author, sat near Centerpoint Plaza in downtown Tempe, AZ in 2020 during covid-era graduations as a way to celebrate during social distancing. Photo courtesy Downtown Tempe Association.

Image 4: C-3PO and R2-D2 welcome visitors to write their thoughts about pizza on a whiteboard in Ross-Blakley Hall. Photo by Larry Ellis.

Image 5: Students in an ASU class use sidewalk chalk as "guerrilla marketing" to help teach about gender and violence. Photo courtesy ASU News.

Image 6: Local news reported on Tempe's infamous graffiti artist. Screenshot from ABC 15 video.

Image 7: "Kilroy is here" graffiti. Photo courtesy Larry Ellis.