If you build it they will come

Teaching Milton in an Arizona prison

I. Alienation and Postmodernity

The alienation is inherent in the architecture. One heavy metal, dull green door slides automatically shut. Once its motion ceases, the identical door opposite automatically slides open. The Arizona sun raises a blinding glare from the white pebbles, grey concrete and beige barracks, so that the eye is forcefully, irresistibly focused on the hundreds of garish, dayglo orange jumpsuits moving around the yard. The identical uniform initially makes it hard to distinguish the human individuals who wear it, but sufficient squinting reveals a strict segregation by color: black over there, white over here, brown in the middle.

The first step into the yard of Florence State Prison produces an inchoate flush of anxiety—something akin, I imagine, to a mild panic attack. As we crossed the yard to the hut where we would be teaching, my more experienced colleague Joe Lockard, the instigator of Florence’s education program, must have sensed my discomfort. His whispered words of reassurance gave voice to my own feelings: “this is a different world.”

Before physically entering the prison, I’d presumed that I knew a fair bit about such places. Any professor of humanities, in any twenty-first-century American university, will be able to speak confidently about the “carceral society.” They will be familiar with at least the grisly opening pages of Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, and many of them will have studied applications and expansions of Foucault’s theories in the works of thinkers like Judith Butler and Giorgio Agamben. There is something approaching a consensus among intellectuals that the prison is the paradigmatic institution of postmodernity.

The academic interest in “carceral studies” arose in response to the penal policies of successive American governments, both local and national. The election of officials like Rudy Giuliani as Mayor of New York City in 1992, and Joe Arpaio as Sherriff of Maricopa County in 1993, were culminations of a long-standing tendency for politicians and the media to appeal to ‘law and order’ as the model solution for social problems.

In practice, this meant mass incarceration, the use of plea bargaining to bypass the presumption of innocence, the ruthless enforcement of “quality of life” violations, the deployment of “stop and frisk” tactics in minority neighborhoods, mandatory sentencing such as “three strikes” laws, increased use of private prisons, harsher conditions within jails and prisons, the extension of the prison beyond its walls through the increased use of probation, parole and house arrest, the universal presence of surveillance cameras, and the seeping of criminal law into the immigration and family systems.

All these developments consolidated the formative influence of carceral ideology on postmodern American culture. Even within such remote ivory towers as literary studies, the influence of the prison is unavoidable today, even as prisons themselves are physically hidden from public view. As I write, in the middle of 2020’s long, hot summer of demonstrations, riots and iconoclasm, the baleful consequences of such carceral ideology are being violently enacted on the streets of American cities. Yet this is merely the eruption of tendencies that have been building, with increasingly obvious alacrity, for at least three decades.

The misguided “war” on crime waged by presidential administrations from Nixon through the younger Bush involved a radical departure, in qualitative and quantitative terms alike, from the previous role of the criminal justice system. Policing and sentencing alike intensified to a degree that rendered law enforcement random and indiscriminate, at the same time as its powers were exponentially expanded. Between 1970 and 2010 the number of people imprisoned in the USA increased by 700%, amounting to 25% of the world’s prison population.

A burly young man wanted to know how I’d felt on first entering the prison. I was able to answer without hesitation: “intimidated."

The idea of crime as a matter of individual guilt or innocence, which could be combatted by the moral reform of the individual criminal, was largely abandoned in practice. A “war” is not fought against individuals, but against entire societies. The sheer scale of the boom in imprisonment means that the subjective condition of the individual criminal was removed from consideration in either the prevention or the punishment of crime, just as the subjective opinion of the individual judge was replaced by the objective, efficacious power of mandatory sentencing requirements.

Throughout its history, Arizona has occupied a vanguard position within carceral ideology. With the indigenous population not subdued until the late nineteenth century, the state has always been a carceral society, constructed in the image of the prison even before its formation. It was the site of POW camps during both World Wars, and today Arizona’s economic dependence on the prison-industrial complex, and the widespread social and ideological effects of such dependence, are deeply embedded in the state’s culture.

Yet the prison’s influence is as impalpable as it is universal—hence the almost physical discomfort I felt as the green door slid shut behind me. Professor Lockard was right: we had entered a “different world.” Today, prison is a place deliberately designed to be alien to the surrounding environment. In twenty-first century America, prisons are built as far out of sight as possible—a significant departure from the age of Enlightenment, when they were deliberately placed near the centers of large cities. Physical isolation means that sentences effectively include exile from family and friends. It is hardly surprising to find that that the physical transition from without to within the prison walls produces a feeling of alienation.

The prisoners who became students in our classes knew this very well. I gave my prepared lecture on the late poetry of John Milton, then asked for questions. To my discomfort, the first inquiry was about me. A burly young man wanted to know how I’d felt on first entering the prison. I was able to answer without hesitation: “intimidated.” A ripple of laughter went around the room, the students nodded emphatically—“that’s right, that’s how we feel too!” Paradoxically, the shared feeling of alienation established a common ground of experience.

In prison, subjective feelings of alienation are not necessarily produced by the individual psyche; they are ineluctably provoked by the physical surroundings. This process affects the guards as well as the prisoners: employment in a correctional facility is often called “a life sentence in forty-hour shifts.” Even the most casual of visitors will experience a relatively mild, but absolutely unmistakable, sense of alienation on entering a twenty-first century American prison. It is a psychosomatic experience in the classical sense: physical as much as psychological.

"In post-human society, crime is no longer caused by a metaphysical evil that demands physical retribution, as it was in the Middle Ages."

Involuntary effects are tyrannical. They bypass the will, they ignore reason. They are “performative” in the sense famously described by Jean-Francois Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition. When a priest declares a couple married, for instance, an objective effect is achieved by the pronouncement of the words. The couple’s married status is not susceptible to rational dispute. Nor is it dependent on the human will, whether that of the couple, the priest, or any observer.

According to Lyotard and his legions of followers, the postmodern era is defined by the predominance of the performative sign. The rational, independent, human subject of the Enlightenment has been overwhelmed by the efficacious power of representation. Our thoughts, attitudes and actions are no longer our own. They are alien to us, and they rule over us in the form of performative symbols. The self-reproducing, objectively efficacious icon known as “money” is only the most obvious example.

Thinkers like Donna Haraway argue that this dissolution of the rational, autonomous subject heralds the dawn of the “post-human” age. In post-human society, crime is no longer caused by a metaphysical evil that demands physical retribution, as it was in the Middle Ages. Nor is crime committed by an individual potentially susceptible to psychological rehabilitation, as it was in the modern era. In the post-human carceral society, crime is produced by objective, material conditions whose influence on human thought and behavior is performative, and thus irresistible.

II. Milton Imprison’d

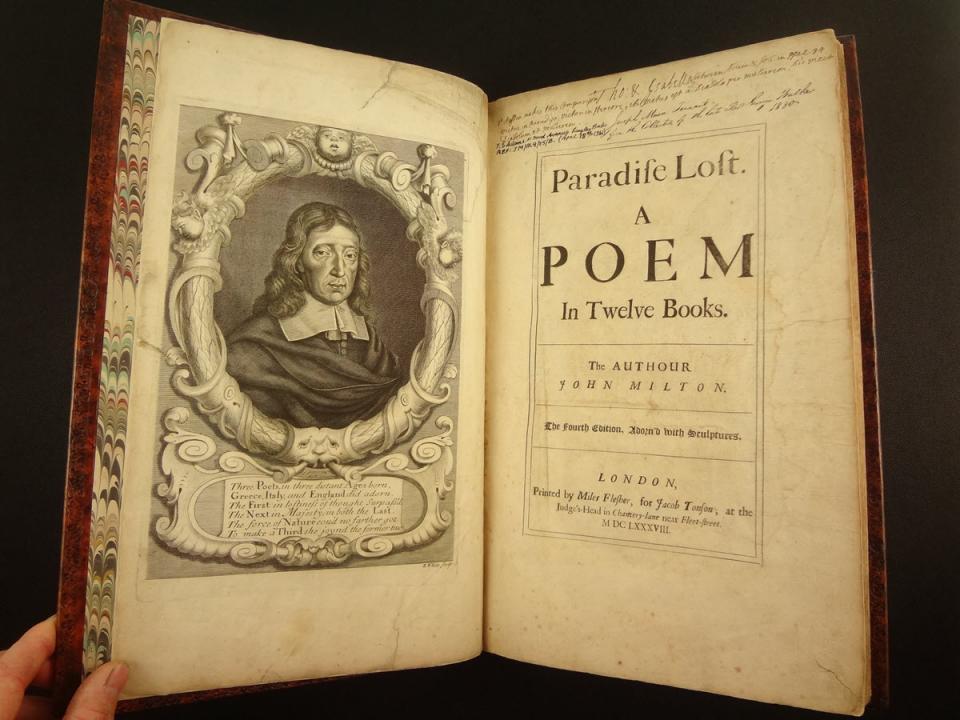

I selected John Milton as the topic for the classes I taught in Florence, partly because I thought some of the students might already know his work. But there were thematic reasons too. Milton’s late, great works—Samson Agonistes, Paradise Lost and Paradise Regain’d—devote thousands of lines to the debate between predestination and free will. They ask to what extent are our actions pre-determined by external circumstances, and to what extent are they freely-chosen courses of action?

Milton’s interest in such questions was political as well as theological. He wrote his final poems after witnessing the defeat of the English Revolution—the cause to which he had consecrated the best years of his life, and whose victory he had assumed was predestined, because it was ordained of God. The defeat of this cause concentrated Milton’s attention on what Christopher Hill calls the “experience of defeat.” With the Restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, Milton even suffered a brief period of imprisonment as a regicide.

In their different ways, each of his final works takes imprisonment as its theme. The first two books of Paradise Lost take place in Hell, which Milton calls a “prison” and a “dungeon.” Samson Agonistes is concerned entirely with the psychological experience of a prisoner. Yet Milton is rarely included in the canon of “carceral literature,” and this reflects an inadequacy in the academic response to mass incarceration: in general, carceral studies have yet to be extended very far back into the past.

Although the prison experiences of Restoration dissenters like John Bunyan and John Milton were presumably influential on their aesthetics, few critics have studied that influence in any detail. It was not until I taught Milton in a prison, and was therefore able to assimilate the prisoners’ perspective on his work, that I was able to see how profoundly the themes of alienation and incarceration inform his sensibility.

For instance, in the opening books of "Paradise Lost," Satan’s experience combines imprisonment in Hell with alienation from Heaven, and the two experiences are shown to be essentially identical. As the poet and Satan himself both understand, this imprisonment is subjective as much as objective: “round he throws his baleful eyes / That witness’d huge affliction and dismay / Mixt with obdurate pride and stedfast hate” (1.56-58). The fallen Satan experiences subjective phenomena like pride and hate as objective things that he can physically see. The first effect of his imprisonment is the alienation of his own psychological processes.

Milton makes it clear that Satan has committed a crime, and has been justly punished by eternal imprisonment. Paradise Lost goes on to explain how the Fall necessitates the rule of the Law, the Old Dispensation between Moses and Christ, during which humanity’s postlapsarian impulse to sin must be forcibly restrained by religious and civil law alike. For most of its history, the American penal system was run on the assumption that the purpose of law is to restrain and punish the individual’s sinful tendencies.

III. Frank Gehry and the Enronization of Prison Architecture

The postmodern carceral system of mass incarceration departs from that model. Quite apart from the factors mentioned above, the system is increasingly run for profit, and therefore has a vested interest in the production and reproduction of crime. As its failures grow harder to deny, however, there are a few encouraging straws in the wind. The Florence prison where I taught is to be closed down. The official line is that most prisoners will be moved just a few miles down the road to the neighboring Eyman complex, but the town of Florence has depended on the prison-industrial complex for its entire history, and the citizens are naturally nervous.

Following Governor Ducey’s announcement of the closure, the town of Florence issued a collective statement noting that, “Florence State Prison is a historic landmark and is woven into the very fabric of Florence. Its tower is proudly and prominently featured on our Town Logo and official seal.” They announced their commitment to “a solution that is appropriate for our community, our residents, and the many employees that call Florence home for eight to twelve hours per day.”

"Each stage in the evolution of carceral ideology has been closely paralleled by developments in prison architecture, from the underground dungeons of the Middle Ages, through the panopticon of the Enlightenment, to the wire-and-glass barracks that I found so alienating at Florence."

The forlorn tone suggests that the citizens of Florence view the future of penal institutions with considerable pessimism. There are signs that they may be correct: the world-wide street protests of 2020, with their calls to defund the police, indicate a serious public revulsion from the carceral society, and it may be that the era of mass incarceration is drawing to a close. The decriminalization of marijuana alone is likely to result in a significant diminution of the prison population.

Each stage in the evolution of carceral ideology has been closely paralleled by developments in prison architecture, from the underground dungeons of the Middle Ages, through the panopticon of the Enlightenment, to the wire-and-glass barracks that I found so alienating at Florence. It seems likely, therefore, that the recent interest taken in prison design by Frank Gehry, perhaps the leading postmodernist architect, is a significant sign of things to come.

Gehry has been involved in the design of correctional facilities since 2016 when, at the invitation of George Soros’ Open Society Foundation, he participated in a study on prison design that was publicized by the documentary film Frank Gehry: Building Justice. Gehry espouses a humane approach to prison architecture, taking his students to view prisons without cells or bars in Norway and asking: “What if we start treating people like human beings—what would prison look like?”

Nothing like Florence State Prison, one assumes. Yet Gehry’s involvement in correctional architecture is not without its ironies. As one irate Twitter user pointed out: “everything he builds is a prison.” As the inheritor of the modernist, Bauhaus school of architecture, Gehry shares responsibility for the spread of buildings that resemble purely functional “living machines.” Modernist and post-modernist architecture in general are frequently criticized as soulless and alienating, and it is arguable that that asking Gehry to design prisons is merely an acknowledgment of carceral ideology’s widespread influence.

The idea of a prison without walls is not unprecedented. Until the reforms of the Enlightenment the prison’s boundaries were porous, with people and goods travelling regularly in both directions. If Gehry’s architectural advice is followed, that model may soon return, and the physical and ideological distance separating prisons from society will be reduced. Any humane person should welcome this as progress. Yet it is hard to ignore the nagging question of which way the influence is likely to flow. Will prison become more like the outside world? Or will things move in the other direction?

Some would say that the world has already been remodeled in accordance with Gehry’s architectural vision. In a 2006 review of Sidney Pollack’s documentary Sketches of Frank Gehry, Phillip Kennicott quotes Jeffrey Skilling, CEO of the notorious Enron corporation, speaking in 2001:

The uniqueness of Frank Gehry's work is the blending of the functional with the artistic to create an innovative product… This is a quality Enron relates to every day as we question traditional business assumptions and embrace innovative solutions. We are pleased to help showcase Frank Gehry’s genius.….

Such commercial language seems to have affected Gehry’s conception of himself. He happily repeats the criticism that his work amounts to “logotecture,” an architectural form in which the “logo” or brand becomes more significant than the building. He is often castigated as the ultimate purveyor of symbol over substance. His defenders generally concede the point, but retort that it is precisely his grasp of the central importance of the symbol in postmodernity that renders his work so instantly redolent of the twenty-first century Zeitgeist.

"If prison is indeed the model social institution, a transformation in the paradigm of the prison must cause ripples throughout society."

Gehry’s architecture both reflects and advances the transformation of a production-based economy, organized around the making of useful things, into an exchange-based system organized around the transfer of money. His Guggenheim museum in Bilbao facilitated that city’s transition from the Basque industrial powerhouse to an economy based on branding, tourism and service. It is only natural that Enron, the corporation infamous for taking the autonomous power of financial representation to a whole new level, would be an enthusiastic promoter of Gehry, sponsoring a huge Guggenheim show devoted to his work. As Kennicott perceptively remarks:

Skilling’s description of Enron parallels Gehry’s architecture very closely. It always questions traditional assumptions; it always embraces innovative solutions. And to some, it suggests a giddiness that seduced many Enron investors: It seems to stay up, as if by magic, hiding its inner structure, glistening on the outside, exuberant and strong.

What would it mean if Frank Gehry’s influence became predominant in prison design? The first effect would be to blur the distinction between prison and the world outside. Prisons would soon come to resemble all the other concrete boxes that fill city centers. Glass windows would replace iron bars, perimeter fences would supplant stone walls, prisoners would wear civilian clothing. Instead of imposing alienation, prison architecture would aim to blend prisons into external environment.

In Discipline and Punish Foucault pointed out that, “factories, schools, barracks, hospitals… all resemble prisons.” If prison is indeed the model social institution, a transformation in the paradigm of the prison must cause ripples throughout society. Such a transformation may even have effects within the psyche. That is perhaps the main reason to welcome the “carceral turn” in the humanities. By studying the history of literature about prison, by reading the writing of prisoners themselves, and by teaching the humanities within prison, we can attempt to influence this coming change in a benign direction.

Image 1: An aerial view of the Arizona State Prison complex in Florence. Photo by Alan Levine on Flickr. Image in public domain.

Image 2: A sign fence at Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio's infamous "Tent City" in Arizona in 2016. Photo by ~filth~filler~ on Flickr. Used under CC 2.0.

Image 3: A 1942 painting of a WWII Japanese internment camp: Poston Relocation Center in Arizona. Painting on cardboard by Tom Tanaka. Photo by Dark Tichondrias on Wikipedia. Used under CC 3.0.

Image 4: A 1688 printing of Paradise Lost, Book 1 by John Milton. Photo by Isaiah Cox on Flickr. Used under CC 2.0.

Image 5: John Milton visiting Galileo when a prisoner of the Inquisition. Oil painting by Solomon Alexander Hart, 1847. Image courtesy of Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons.

Image 6: The interior of Halden Prison in Norway, considered one of the most humane prisons in the world. Photo by Justis- og beredskapsdepartementet via Wikimedia Commons. Used under CC 2.0.

Image 7: The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, designed by architect Frank Gehry. Photo by Riina on Wikimedia Commons. Used under CC 3.0.