'Dear Himalayas': Alum Bringing Lyric Medicine to Nepal

Editor's Note: In this issue, we’re spotlighting MFA alumni in recognition of the ASU Creative Writing Program 30th anniversary celebration. We’ll highlight alumni from other areas in future editions. Stay tuned.

Samyak Shertok dialed the familiar pattern of numbers over and over as the sun came up in Tempe. Each time the result was the same: no answer.

He told himself the phone lines were down, or busy. Finally, several hours later, his mother answered. The connection lasted only a few minutes, but it was enough.

After five hours of trying, when the call

finally goes through & I hear

my mother’s voice, I learn

how to unash my lungs.

For many people with loved ones in Nepal, the morning of April 25 brought tremendous anxiety and uncertainty.

A magnitude 7.8 earthquake, centered 50 miles northwest of Kathmandu, rocked the small Himalayan country. Violent aftershocks followed for many days, including a second quake of 7.3 magnitude, centered 40 miles east of Kathmandu just two weeks later.

More than 8,000 people died as a result of the temblors, and more than twice as many have been injured. Recovery efforts remain underway.

Shertok, an ASU English graduate (MFA 2014) living in Tempe, did eventually confirm that his immediate family had escaped harm. But others in his circle were not so fortunate.

“My niece lost her daughter in the house next to the one I grew up in," he said. "The entire family of our next-door neighbor got caught when the house collapsed on them."

Shertok’s mix of emotions after the quake—his anguish at not being able to reach his mother, his nearly sickening relief when he did—overwhelmed him. So he did what he usually does at times like these.

He wrote about the terror-filled hours spent trying to reach his family. He wrote about the disorientation of seeing the destruction on television. And he wrote about his growing frustration at being helpless, 8,000 miles away.

Dear Himalayas, this morning I have nothing

to offer you. Not even a butter lamp

or your one-thousand-year-old gods

Shertok published the poem “Aftershocks” on May 6 in the Nepal-based La.Lit magazine, an English-language literary journal.

He also read the poem aloud at a vigil held by ASU’s Nepalese Student Association. Many in attendance—Nepal-born and otherwise—said that it had affected them deeply. One woman said the poem gave her goosebumps.

Shertok was born in the small Nepalese community of Phalam Sangu in the Sindhupalchok district. The village had no electricity, and he recalls his father’s transistor radio as their only access to technology.

“I remember being very fond of [the radio] and carrying it around when my father was not listening to the 5:00 p.m. news, its strap slung around my neck,” he said.

No televisions or video games meant that kids from Shertok’s village made their fun where they found it. He described a typical weekend day.

The Balephi River flowed just south of our house, where we went to swim and wash our clothes on Saturdays. The whole village would gather on the banks of the river. Men and boys crossed the rivers trying to prove their worth to their peers and perhaps impress some of the women. My brother was one of the most skillful and fiercest swimmers, but I could barely string three strokes. So, I used to watch him and other boys cut the currents from the shore in awe and envy.

Shertok may not have been a good swimmer, but he did have a way with words. He attended Brigham Young University in the U.S., majoring in English. From there, he was accepted into ASU’s competitive, highly ranked creative writing program, where he earned his Master of Fine Arts in fiction writing in 2014.

Since then Shertok has been volunteering with Poesía del Sol, the ASU creative writing program partnership with Mayo Clinic. Each week he interviews palliative-care patients and then crafts poems for them based on those interviews.

The program uses what it calls “lyric medicine” to enrich patients’ lives using storytelling. It is premised on the notion that we all have stories to tell, and that in sharing them we can begin coming to terms with difficulties, even disasters.

The concept of using writing—especially poetry—in healing is more than a theory; its efficacy has been demonstrated in multiple studies. Several prominent schools of medicine, including Yale and Mount Sinai, now incorporate poetry into their programs.

Writing seems to be especially effective in dealing with trauma. Perhaps because, as Robert Carroll of UCLA’s Department of Psychiatry puts it, when something immense happens we at first have no words.

“Some catastrophes are so large, they seem to overwhelm ordinary language. Immediately after the . . . tsunami disaster in Southeast Asia, the Los Angeles Times reported the witnesses were literally dumbstruck. Words failed them. They had lost their voices,” wrote Carroll in a 2005 article in the journal Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

According to Carroll and others, language appears to re-wire our brains to process and accept a loss. Words help us cope with what is otherwise unimaginable—and at first unspeakable.

“Our voices are saturated with who we are, embodied in the rhythms, tonal variations, associations, images and other somato-sensory metaphors in addition to the content meaning of the words. Our voices are embodiments of ourselves, whether written or spoken. It is in times of extremity that we long to find words or hear another human voice letting us know we are not alone,” said Caroll.

On April 25—the day of the earthquake, when Shertok was frantically dialing Nepal—a small but strange thing happened. After his call to his mother was disconnected, he tried again. The call was answered, but instead of his mother’s voice, Shertok heard many voices, all speaking at once.

“I heard fragments of their conversations—men, women, children. I felt like I was hearing the voice of the whole country . . . I stayed on the line for about five minutes and then hung up.”

Shertok believes that a technical issue caused the glitch, some telecommunications malfunction in the earthquake-weary region. But the sense that he had, for a moment, been connected with all Nepalese seeking solace and connection, made its way into his poem, which he called a “love letter” to his country.

“This was just another way of saying: ‘Dear Nepal, I'm not sure if I can do anything for you, but I feel your pain and want to sit next to you as you grieve.’"

He said that when he completed the poem, he “felt a great sense of visceral release.”

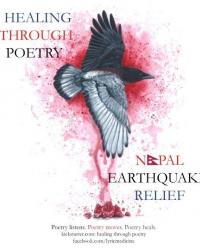

Inspired by the response to his “Aftershocks” poem, Shertok will launch a project in collaboration with the Nepalese Student Association he’s calling “Healing Through Poetry” in Nepal this summer. He’s hoping to crowdfund the effort through a Kickstarter campaign.

To set his vision into practice, Shertok plans to literally go house to house, starting in his home district of Sindhupalchok, talking to the people. He will begin collecting stories and writing poems based on them, similar to what he has been doing for ASU’s Poesía del Sol.

He is also proposing to run poetry workshops for young people, whom he’ll encourage to work through their experiences by writing about them. The project will feature workshop students and community participants in poetry readings at local venues, perhaps even at sites of earthquake destruction.

“While it won't initially provide the victims with tangible aid, it will serve their emotional and psychological well-being in the long run," Shertok said. "Healing Through Poetry strives to help Nepal heal and rebuild through poetry that at once embraces, documents, and transcends this historic tragedy as it is happening."

The Kathmandu sky sliced with unlive

wires. Highways broken like bread

or a body. The Vishnu Temple: a pile

of sandalwood beams & too many prayers.

~

I sit at my desk & stare at the paper

white as the song of the earth

as it splits to womb so many Janakis.

Unable to find words, I write

& rewrite the silence.

My bones caw.

I tremble

until prayer becomes my body.

Note: This story appeared in a condensed version in ASU News on May 22, 2015.

Photo 1: Photo of Samyak Shertok by Rajan Shrestha.

Photo 2: Shertok’s mother and baby cousin pose on the veranda of the family’s house in Boudha, Kathmandu, c. 2006. Photo/courtesy Samyak Shertok.

Photo 3: Devastation after the April 25 earthquake in Nepal. Photo/ReSurge International on Flickr.

Photo 4: Healing Through Poetry poster art by Arden Ellen Nixon.

Header background image from the 1930s: ASU's iconic Palm Walk. UP UPC ASUB P343 #26