A note from the editors

Making it public

For pleasure has no relish unless we share it.

—Virginia Woolf

With the establishment of spaces of public/academic engagement in the Library of Congress, the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, and the Smithsonian Institute in the 1970s, what has come to be called “public sector folklore” (public folklore for short) was established as a major sub-discipline of folkloristics. Carrying on the traditions of earlier fieldworkers who had gone beyond the simple collection of data to “advocate for the folk,” public folklorists take the practice of folklore from the university into the public square, where both scholars and members of folk communities collaborate in activities tied to the preservation and representation of local culture.

And so with public humanities. Broader in scope than and encompassing much of public folklore, public humanities employs similar strategies to connect academic endeavor to the public good. Chicano playwright Luis Valdez comes to mind. In the 1960s, he established El Teatro Campesino, a travelling theater troupe that put on performances in support of Cesar Chavez’ United Farm Workers Union. The Teatro is active to this day.

In our own uncertain times, public humanities have continued to function to inform, enrich, and in some cases, entertain us. An example: the West Virginia Humanities Council, directed by ASU Department of English alumnus Eric Waggoner (PhD 2001), offers an online program of West Virginia poets reading their work from their homes. Waggoner also recently spearheaded an additional WVHC offering: digital online readings of audio fiction in the “Mysterious Mondays” series, which began on April 6. Waggoner explained the adjustments the council had to make in its outreach due to the coronavirus pandemic:

What we like to do is bring the humanities to people everywhere in West Virginia, no matter where they live. Where possible, we like to do that through face to face and onsite settings. Obviously, now, safety conditions indicate that we should postpone those sorts of events. It’s the smart and the reasonable thing to do.

Virtual poetry readings and the “Mysterious Mondays” series are among the “new digital online programming” Waggoner and his staff, like many humanities leaders, have initiated to fulfill the council’s public humanities mission in the face of national emergency.

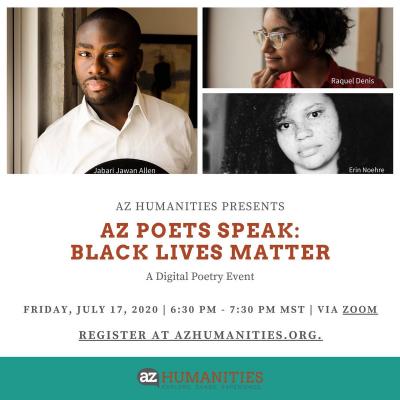

Closer to home, Arizona Humanities has continued to engage the public through its virtual AZ Poets Speak series, which featured many ASU English alumni, faculty, and students. Series events explored Vanishing History (April 29), The Body (May 13), and Black Lives Matter (July 17). The council also provided emergency grants to non-profit and humanities cultural organizations through the CARES Act.

In our own “backyard,” so to speak, you can read in this newsletter issue about how ASU alumnus and educator William “Wonderful” Jenkins took his poetry to the streets of Tempe’s Maple-Ash neighborhood, becoming an icon of local culture before his passing in August of last year. Alberto Ríos, Regents Professor in the Department of English and Director of the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing, plans to translate ASU’s Hayden’s Ferry Review “into as many languages as possible.” In pursuing her PhD at ASU, Elizabeth “Bootsie” Martinez participated in a university program in which graduate students are allowed to gain experience teaching in state prisons.

We have dedicated this issue of the newsletter to these and other accounts of the engagement of university and non-university communities that defines the public humanities in our department. We hope you enjoy.

Image 1: Courtesy image of newsletter editor Larry Ellis.

Image 2: Luis Valdez at Teatro Campesino with the cast of "Valley of the Heart" in a 2013 Q&A. Photo credit Steve Rhodes on Flickr.

Image 3: On July 17, Arizona Humanites presented a Black Lives Matter event in its AZ Poets Speak series.