From the archive to the page

Devoney Looser is keeping up with the Porter sisters

Devoney Looser, Regents Professor in ASU’s Department of English, has inspired me since I met her. Every time I learn something new about her, I think, “Okay, now that’s the coolest thing about her.” From her roller derby persona as Stone Cold Jane Austen to her writing on sports for Slate to her lifelong fascination with Jane Austen, Looser’s devotion to her interests is astounding.

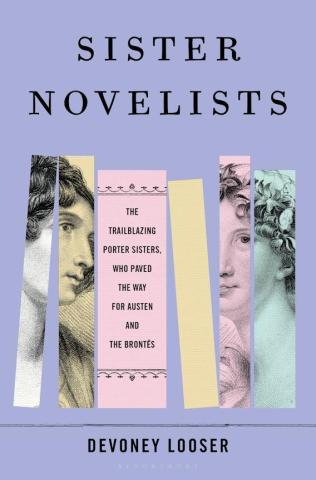

Her latest adventure has been to bring to light the lives of two sister novelists forgotten in both the academy and pop culture. Having worked on this book on and off for about twenty years, she is ready to introduce the world to sisters Jane and Anna Maria Porter in her new book "Sister Novelists: The Trailblazing Porter Sisters, Who Paved the Way for Austen and the Brontës" (Bloomsbury). I know about these two authors from taking one of Looser’s classes, “Jane Austen and Her Contemporaries,” about a decade ago. However, I still remember reading (and loving) a required text for the class: Artless Tales; Or, Romantic Effusions of the Heart by Maria Porter, written at an early age.

Looser was one of ten fellows selected to spend October to November 2021 at an exclusive writing residency at the Rockefeller Bellagio Center, a stunning 50-acre property at Lake Como in northern Italy. The Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center has hosted thinkers from all over the world providing them with a beautiful space to work and time to complete their projects, as well as opportunities to learn from and interact with other great minds. This residency allowed Looser to make edits to Sister Novelists, heralding the completion of the book.

Sister Novelists is a biography of two British writer sisters, born near the end of the eighteenth century, who wrote in the early nineteenth century. Jane and Anna Maria Porter both wrote interesting and important works of historical fiction. Looser notes that no full-length biographies of the sisters exist. A large number of letters do exist, however, and Looser was able to access and use these to understand the sisters’ lives, careers, and relationships.

Research was not easy, however, especially during the pandemic, which resulted in the closing of many libraries for an extended time. Another effect of the pandemic was the necessary shortening of the book in draft. Looser knew she’d need to cut the draft from its original 1,000 pages. First, she was asked to make deep cuts to accommodate pandemic changes in shipping, printing, and paper. This necessitated a change in gears, because she’d hoped to spend her Bellagio residency “fine-tuning the prose and smoothing rough edges” but instead had to “slash the content by almost one half.” The writing world of today has its own complications about which Maria and Jane could not have imagined!

Looser was able to use her time at Bellagio to shorten her manuscript to the needed length. She had to balance cutting down stories of the Porter sisters' lives with trying to give a comprehensive picture. The book will be released this October. Looser credits Bellagio and her community/support team with helping her change, craft, and cut the book down to size. When we spoke over Zoom earlier this year, her excitement about the book was contagious.

Note: The interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Mollie Connelly-MacNeill: Can you describe your first experience reading the Porter sisters?

Devoney Looser: I think that I started reading their unpublished letters and one of Jane Porter's novel’s Thaddeus of Warsaw, from 1803, at the same time. I was going to the letters because I was writing a book about women and old age, and Jane Porter lived into her seventies. I wanted to see what happened to her career as she aged. As I read the letters between Jane and Anna Maria Porter I just got sucked into the sisters’ lives, and then to reading their works.

MC: What was the most meaningful part of your time at Bellagio Center?

DL: The most meaningful part was the incredible opportunity to focus on a project with such support. I mean, I knew that’s what it was going to be, going into it. It was very meaningful to have the support, time, and space to get the work done. What I didn't realize in advance was how amazing the community would be. There were ten of us fellows there, and under pandemic circumstances we all stayed for the whole month. Because we were a pandemic cohort, all of us spent the month together and we bonded incredibly well. Each evening, there was someone giving a lecture. We had meals together and we had camaraderie and conviviality, and that's very much the spirit of the center, too. You worked very hard during the day, and you took advantage of the beauties of the property and the town, but in the evening we spent time with the community and that was as meaningful as anything.

MC: Did it feel a little "Decameron"-like?

DL: It felt like something out of a fairy tale. I've never been taken care of so well in my life, and there were moments where, especially coming out of the pandemic, I think many of us felt quite guilty. The director kept saying, “You deserve this,” and “You were brought here to have the opportunity to finish this project that you’re working on, which we believe in.” And, “We selected you because we believe in your project and you deserve these kinds of support to complete the work.” They felt like luxuries, and I'm not sure if I deserved to be treated so well.

MC: What was your approach to taking a 1,000-page manuscript and reducing it down to 600 pages?

DL: It's hard for a first biography of two once-famous sisters who are now unknown. It was a lot of responsibility to feel like whatever part of their lives I'm not telling is now going to be left up to somebody else to do, and so I need to choose the parts that are going to, with any luck, make people want to know more, and so that's what I tried to do. But that was quite hard.

Any of us thinking about the years of our lives that we would and wouldn't want narrated—and it’s two sisters, so it’s two lives that I’m trying to intertwine–knows there are necessary omissions. I knew the book was too long, and that I’d need to make cuts, but it felt really difficult to know which parts were the most important parts. I hope I made the right choices for this moment! It’s the first biography of the Porter sisters—and, with any luck, not the last. The time at Bellagio allowed me to have some insight and conversations with others about what questions readers might have as their most burning ones for a first biography. The fellows were very helpful. It was incredibly useful to have their perspective about what parts of the story resonated and what parts they wanted to know more about. They were an incredible group of interlocutors and listeners and people giving feedback—artists, architects, a social scientist who worked on autism, the head of a non-profit foundation, etc. It was just an incredible range of thinkers and creators from all over the world.

MC: What did your day-to-day look like during this experience?

DL: I had all the technology I needed, and I had a very specific goal in mind. I had the most beautiful study space imaginable. Looking at Lake Como and the mountains and the ferry and the church with its bells that would go off—I mean it was just the most incredible place to feel at peace with what was actually quite an anxiety-provoking writing and editing task.

MC: What in your opinion is the value of reading the Porter Sisters in an Austen world? Meaning, if you have an Austen book and a Porter Sisters book sitting there, why pick up the Porter over the Austen?

DL: I think that there are two ways I could answer that. One is that I think it’s apples and oranges. The Porters were writing didactic historical fiction, not comic novels of manners like Austen’s. In their subgenre of fiction, the Porters were really important innovators before Sir Walter Scott, and they’ve been wrongly forgotten. Readers could pick up a novel by the Porter sisters when they wanted something different from Austen. But all of them are writing at exactly the same time, and there are many confluences among the careers of the two Janes and Maria.

But another reason someone might pick up the Porters’ books is for a new perspective on Austen’s era. Jane Porter was the most famous Jane writing in the early nineteenth century, not Jane Austen. I understand and appreciate why Austen’s novels have endured differently from the Porters’. What a nineteenth-century British author thought about sixteenth-century Portugal [as in Anna Maria’s Don Sebastian; Or, the House of Braganza] can be hard to parse! But I think even for people who aren’t history buffs, there’s still something there in the Porters’ historical fiction that’s fascinating and moving.

MC: What was one highlight of writing the book?

DL: The sisters’ letters to each other are so gripping to me, that as I was reading them, I could forget what century I was living in. When you are reading unpublished private letters, it's like being let into a secret conversation. You're not sure whether you should or shouldn't be reading it! But reading other people's mail—reading dead people's mail—was the highlight of writing this book. There were so many incredible secrets of their lives and their challenges as authors hidden in them. I got to record the sisters’ love for each other, their passions, their successes, their disappointments. They were celebrities in their own day, and they knew all of the movers and shakers then. I’m so grateful that the perspectives on what they saw, which they shared with each other in these candid letters, were preserved. That was what was the most exciting part of writing this book—bringing these sister novelists’ secrets and struggles from the archive to the page.

Image 1: Cover of Looser's forthcoming book, "Sister Novelists" (Bloomsbury, 2022).

Image 2: Looser at the Bellagio Center in Italy, 2021. Photo by Alice Luperto.

Image 3: Looser holds two copies of Jane Porter's novel of William Wallace, The Scottish Chiefs. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU.